Article by Unnati Singh

For Sikkim, a state whose mountains echo with Buddhist prayer flags and monasteries,

history is not something stored in museums, it is lived every day. From Rumtek to

Pemayangtse, Buddhism here is not just faith but identity, culture, and moral order. It is in this

context that the recent return and public exhibition of the sacred Piprahwa relics takes on a

deeper meaning for Sikkim and the wider Himalayan Buddhist world.

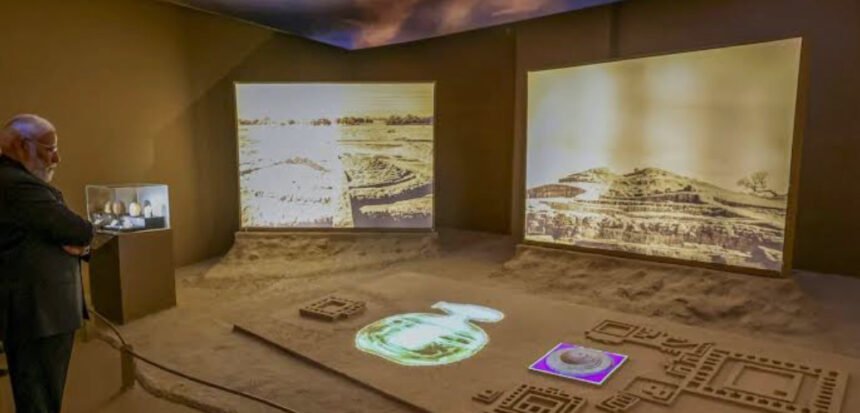

On 3 January 2026, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the Grand International

Exposition of the Sacred Piprahwa Relics in New Delhi, marking the first comprehensive

public display of these relics in more than 125 years. The exhibition, titled “The Light & the

Lotus: Relics of the Awakened One,” is not merely an archaeological event. It represents

India’s renewed civilisational responsibility toward Buddhist heritage, a responsibility that

resonates strongly in Sikkim, one of India’s most deeply Buddhist regions.

The Piprahwa relics were discovered in 1898 at a stupa in present-day Siddharthnagar in

Uttar Pradesh. They include bone fragments believed to belong to Lord Buddha, housed in

crystal and steatite caskets, accompanied by gemstones, gold ornaments, and a sandstone

coffer. What makes them especially sacred is a Brahmi inscription linking the relics directly to

the Śākya clan, the Buddha’s own lineage, establishing Piprahwa as one of the most

important sites in early Buddhist geography. For Buddhists, these are not objects of curiosity.

They are living symbols of compassion, non-violence, mindfulness, and moral discipline,

values that shape monastic traditions in Sikkim and across the Himalayan belt. When monks

in Rumtek or Pemayangtse chant the sutras, they are spiritually connected to the same

civilisational roots that Piprahwa represents.

For more than a century, these relics remained scattered and largely inaccessible, reflecting a

colonial pattern where sacred Asian heritage was removed from its cultural context. India’s

decision to reclaim and present these relics publicly marks a historic shift.Prime Minister Modi

described the exhibition as the “return of India’s heritage itself,” underscoring a national

resolve that sacred history will no longer be confined to elite institutions or foreign custody.

This is not about nationalism alone, it is about dignity. For Buddhist communities, including

those in Sikkim, this represents moral and spiritual restitution.

The modern world presents a new danger to religious heritage: commodification. In May

2025, jewels linked to the Piprahwa relics surfaced in international auctions, raising alarms

that sacred objects were being turned into luxury collectables. This is a deeply troubling trend

for Buddhist societies, where relics are not owned by individuals but entrusted to communities

and monastic orders.

India’s Ministry of Culture intervened in July 2025, ensuring that the relics were returned after

127 years through legal, diplomatic, and moral action. The repatriation was not just

procedural, it was civilisational, asserting that sacred heritage cannot be treated as a financial

asset but must remain rooted in faith and collective memory. For Sikkim’s monks and lay

followers, this stance reflects the Buddhist principle that spiritual objects exist for ethical and

communal good, not profit.Sikkim has long served as a bridge between Indian Buddhism and the wider Himalayan world,

Tibet, Bhutan, Nepal, and beyond. The Piprahwa initiative strengthens this bridge. By

presenting Buddhist relics with scholarship, respect, and public accessibility, India is

positioning itself as a responsible custodian of shared Asian heritage. This has direct

implications for Sikkim. As Buddhist tourism grows, pilgrims from East and Southeast Asia

increasingly look to India not only as the land of the Buddha’s enlightenment but also as the

guardian of his legacy. When India curates relics with dignity, it enhances Sikkim’s cultural

stature as part of that living Buddhist civilization.

The Piprahwa exhibition also reflects a new model of cultural diplomacy, one rooted not in

spectacle but in ethical continuity. Shared Buddhist heritage is becoming a bridge across

Asia, a universal language of peace, and a source of India’s soft power. For a state like

Sikkim, which thrives on cultural tourism and spiritual exchange, this strengthens India’s

credibility in the Buddhist world. It reinforces the idea that India does not merely claim

Buddhist history, it protects it.

Perhaps the most powerful message of the Piprahwa initiative is that Buddhism is not just

about the past. By restoring and honouring these relics, India is projecting Buddhist values as

a moral compass for a troubled global order, one marked by conflict, consumerism, and

cultural erosion

For Sikkim, where monasteries continue to educate, heal, and guide communities, this is a

reminder that spiritual heritage is not static. It shapes governance, social harmony, and the

way societies treat one another. The return of the Piprahwa relics is therefore not just an

event in Delhi. It is a reaffirmation of India’s Buddhist responsibility, one that echoes all the

way to Sikkim’s hills, prayer halls, and people.